CHILDREN'S MINISTRY COOKING CLASS

LEARNING TO REVERSE TYPE-2 DIABETES

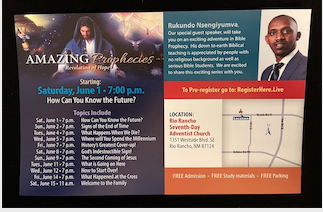

Amazing Prophecies Seminar

June 1 - 15, 2024 from 7-8 p.m.

(Everyday except on Mondays & Thursdays)

General Church News

North American Division News

http://adventistchurchconnect.com/rssscript.php?level=division&orgid=AN1111

World Church News (click on underlined title)

Adventist News Network

|

[Photo courtesy of Liberty Magazine] Long before he began a 35-year run as editor of Liberty magazine, Roland Hegstad had a decision to make. That choice helped change the direction of his life from a secular goal of being a sports editor at a daily newspaper to Christian ministry. A veteran denominational worker, Hegstad died June 17 at age 92 in Dayton, Maryland, after a lengthy illness. Pastor Ted N.C. Wilson, president of the Seventh-day Adventist church, said Hegstad "was a wonderful church leader in the area of freedom of conscience and religious liberty. He served with absolute distinction is his capacity as an editor and was an excellent speaker who helped keep a strong focus on the need for religious liberty.” (The full text of Wilson’s tribute is below) Wintley Phipps, who worked with Hegstad when both were at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, said, "When people contribute to your sense of calling, and your sense of worth, they give you more than money could ever buy, and that’s what he did. [Roland] did more than I could ever imagine because of his encouragement and counsel." And Adult Bible Study Guide editor Clifford Goldstein, who followed Hegstad as Libertyeditor, recalled his colleague as someone who "did not just teach me editing. I learned a lot from Roland about just what it meant to be a Christian." College CrossroadsLinfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, had accepted Hegstad as a journalism student; he was promised a sports section editorship for the student newspaper. Walla Walla College, then a small, Seventh-day Adventist school nearly 300 miles to the east in College Place, Washington, also accepted him. (The school became Walla Walla University in 2007.) He was not an Adventist but, as Hegstad told Adventist Review in 1994, his aunt was. During what he called "a family crisis" just before college began, he took the advice of that aunt—Sylvia Peterson—who told the young man he could find answers to questions such as "Is there really a God" at the Adventist school. He earned a bachelor's degree at Walla Walla in 1949, the year he married Stella M. Radke, who survives. Five years later, Hegstad earned a master's degree from the Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary. Beginning as an evangelist in the Upper Columbia Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Hegstad quickly segued into editorial work. In 1954, he became associate editor of These Times, joining the magazine's staff in Nashville, Tennessee. Two years later, he was named book editor for the Southern Publishing Association, which published the journal. In 1959, the Adventist church’s world headquarters called Hegstad to serve as Liberty magazine's editor; he simultaneously served as associate director of the church's Public Affairs and Religious Liberty department. During his tenure, Liberty received the Associated Church Press' "Award of Merit" for general excellence six times, and 80 other awards. In 1971-72, Hegstad also served as interim editor of Insight magazine,the denomination’s journal for high school and collegiate students published by the church-owned Review and Herald Publishing Association. "An Unapologetic Adventist Magazine"Speaking with Adventist Review in 1994, Hegstad said his most important contribution to Liberty wasn't winning awards, but rather establishing "its identification as an unapologetic Adventist magazine." He told William G. Johnsson, Adventist Review’sthen-editor, "When I became [Liberty] editor, the name Adventist did not appear in Liberty, and editorial policy prohibited articles on doctrine or policy." He changed that, though not without opposition—but also not without approbation: "Within a few years, circulation increased from 165,000 to more than a half million." Hegstad added, "I try to bring the wisdom of God's Word to bear on issues and to communicate it, both in print and in illustrations, in a way intelligible to the secularists who make up a high percentage of our readership." One of Hegstad's happiest accomplishments was helping to negotiate the opening of a Seventh-day Adventist publishing house in the former Soviet Union at the height of the "cold war" between the USSR and the West. He viewed the eventual collapse of the Soviet regime and the subsequent opening of much of the formerly communist world to the preaching of the gospel as a "prophetic event." In retirement, Hegstad created and edited Perspective Digest, a lay-oriented theological publication for the Adventist Theological Society. His books included "The Certainty of the Second Coming," written with Edward E. Zinke; "Pretenders to the Throne"; and "The Mind Manipulators." Encouraged, Mentored AuthorsWhile Liberty editor, Hegstad often found and nurtured new writers, including Goldstein, who admitted he "tried to dazzle him with my golden prose," submitting an article on anti-Semitism that was short on detail. "A couple weeks later I get this very blunt, to the point response," Goldstein, who worked with Hegstad for 10 years, recalled. "Roland was not an editor you could bamboozle. He saw right through it. He said you’re a good writer, but you’re lazy. He told me he never expected to hear from me again. I went back, did my research, sent him the article, and he [published] it." Goldstein said Hegstad's editing prowess was legendary: "Long before computers, there was Roland’s famous red pencil. He would red pencil my work, and he was hard on me. But I realized, this guy’s brilliant. Even to this day, decades later, now and then, I’m editing something, and Roland’s voice will pop me into my head." Hegstad's legacy is valued by the current Liberty editor, Lincoln Steed, who knew the family for decades. "Growing up under his editorship—it’s the passing of a giant in Adventism," Steed said. "He filled that role admirably. He was a great technical editor and an energetic force at the time. Roland Rex Hegstad was born in Stayton, Oregon, on April 7, 1926. An eighth-grade teacher in his hometown of Wauna, Oregon, encouraged his writing interests, which continued through high school and at Walla Walla College. Along with his wife of 70 years, Stella, he is survived by a son, Douglas, of Loma Linda, California; daughters Sheryl Clarke and Kimberly Handel; and four grandchildren. Hegstad and his wife were members of Spencerville Seventh-day Adventist Church in Silver Spring, Maryland. |

Survey

The Rio Rancho SDA Church has as one of it goals to establish Small Groups as a ministry to its members and friends. In order to gain an understanding of what kinds of groups would be most desired, a survey has been prepared. We ask you to complete this survey. Click here.

General Conference News continued

THE REAL DESMOND DOSS STORYDesmond Doss - Adventist medic and recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor When U.S. President Harry Truman awarded Desmond Doss the Congressional Medal of Honor on October 12, 1945, he said, "I'm proud of you. You really deserve this. I consider this a greater honor than being president." On April 1, 1942, Desmond Doss joined the United States Army. Three and a half years later, he stood on the White House lawn, receiving the nation’s highest award for his bravery and courage under fire. Of the 16 million men in uniform during World War II, only 431 received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Among these was a young Seventh-day Adventist Christian who refused to carry a gun and had not killed a single enemy soldier. His only weapons were his Bible and his faith in God. President Harry S. Truman warmly held the hand of Corporal Desmond Thomas Doss, as his citation was read to those gathered at the White House on October 12, 1945. “I’m proud of you,” Truman said. “You really deserve this. I consider this a greater honor than being president.” When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Desmond was working at the Newport News Naval shipyard and could have requested a deferment. But he was willing to risk his life on the front lines in order to preserve freedom. He wanted to be an Army combat medic and assumed his classification as a conscientious objector would not require him to carry a weapon. When he was assigned to an infantry rifle company, his refusal to carry a gun caused his fellow soldiers to view him with distain. They ostracized and bullied him. One man warned, “Doss, when we get into combat, I’ll make sure you don’t come back alive.” His commanding officers also wanted to get rid of the skinny Virginian who spoke with a gentle southern drawl. They saw him as a liability. Nobody believed a soldier without a weapon was worthwhile. They tried to intimidate him, scold him, assign him extra tough duties, and declared him mentally unfit for the Army. Then they attempted to court martial him for refusing a direct order—to carry a gun. But they failed to find a way to toss him out, and he refused to leave. He believed his duty was to obey God and serve his country. But it had to be in that order. His unwavering convictions were most important. Desmond had been raised with a fervent belief in the Bible. When it came to the Ten Commandments, he applied them personally. During childhood his father had purchased a large framed picture at an auction. It portrayed the Ten Commandments with colorful illustrations. Next to the words, "Thou shalt not kill" was a drawing of Cain holding a club and standing over the body of his dead brother Abel. Little Desmond would look at that picture and ask, "Why did Cain kill Abel? How in the world could a brother do such a thing?" In Desmond's mind, God said, "If you love me, you won't kill." With that picture firmly embedded in his mind, he determined that he would never take life. However, there was another commandment that Desmond took just as seriously as the sixth. It was the fourth commandment. His religious upbringing included weekly church attendance, on the seventh day. The Army was exasperated to discover that he had yet another personal requirement. He asked for a weekly pass so he could attend church every Saturday. This meant two strikes against him. His fellow soldiers saw this Bible reading puritan, as being totally out of sync with the rest of the Army. So they ostracized him, bullied him, called him awful names, and cursed at him. His commanding officers also made his life difficult. Things began turning around when the men discovered that this quiet unassuming medic had a way to heal the blisters on their march-weary feet. And if someone fainted from heat stroke, this medic was at his side, offering his own canteen. Desmond never held a grudge. With kindness and gentle courtesy, he treated those who had mistreated him. He lived the golden rule, "…do to others what you would have them do to you…" (Matthew 7:12 NIV). Desmond served in combat on the islands of Guam and Leyte. In each military operation he exhibited extraordinary dedication to his men. While others were taking life, he was busy saving life. As enemy bullets whizzed past and mortar shells exploded around him, he repeatedly ran to treat a fallen comrade and carry him back to safety. By the time they reached Okinawa, he had been awarded two Bronze Stars for valor. In May, 1945, Japanese troops were fiercely defending Okinawa, the only remaining barrier to an allied invasion of their homeland. The American target was capturing the Maeda Escarpment, an imposing rock face the soldiers called, Hacksaw Ridge. After they secured the top of the cliff, Japanese forces suddenly attacked. Officers ordered an immediate retreat. As a hundred or more lay wounded and dying on enemy soil, one lone soldier disobeyed those orders and charged back into the firefight. With a constant prayer on his lips, he vowed to rescue as many as he could, before he either collapsed or died trying. His iron determination and unflagging courage resulted in at least 75 lives saved that day, May 5, 1945, his Sabbath. Several days later, during an unsuccessful night raid, Desmond was severely wounded. Hiding in a shell hole with two riflemen, a Japanese grenade landed at his feet. The explosion sent him flying. The shrapnel tore into his leg and hip. While attempting to reach safety, he was hit by a sniper’s bullet that shattered his arm. His brave actions as a combat medic were over. But not before insisting that his litter-bearers take another man first before rescuing him. Wounded, in pain, and losing blood, he still put the safety of others ahead of his own. Before being honorably discharged from the Army in 1946, Desmond developed tuberculosis. His illness progressed and at the age of 87, Corporal Desmond Thomas Doss died on March 23, 2006. He is buried in the National Cemetery, Chattanooga, Tennessee. For more information, please visit the Desmond Doss Foundation Desmond - Doss Council. Statement: Seventh-Day Adventist Church in North America Regarding the Film, "Hacksaw Ridge."The story of Desmond Doss, the first conscientious objector to receive the esteemed Medal of Honor, is one that has inspired generations of his fellow Seventh-day Adventist Church members. As powerfully shared in the upcoming film, “Hacksaw Ridge,” Doss’s strong convictions, his Adventist beliefs, and his unshakeable confidence in God come alive, and hold the promise of inspiring a new generation of believers. While a graphic portrayal of the realities of war, “Hacksaw Ridge” paints a stirring portrait of the resolute manner in which Doss lived his faith, even while living through the horrors of the battlefield. The Seventh-day Adventist Church historically has strongly discouraged its members from bearing arms, and Doss embodied that philosophy. He became the first person to voluntarily enlist and then be granted conscientious objector status, the role in which he contributed to the often-heroic rescue of scores of his fellow soldiers. The North American Division of the Seventh-day Adventist Church appreciates the care and attention to detail brought to the telling of Desmond Doss’s unique, unparalleled story of faith by the filmmakers in the production of “Hacksaw Ridge.”

|